THE WHITE ALBUM LISTENING

PARTY - The Transcript

© 2008 – Cedar Creek

Studios, Inc. / Paul Ingles / Use with permission only/ Contact paul@paulingles.com

INTRO TO HOUR ONE

PAUL INGLES (Host): Here’s a question. What’s the top-selling Beatles album

of all time: Sgt. Pepper, Abbey Road, Meet the Beatles, Rubber Soul?

Uh-uh. It’s 1968’s The Beatles, also known as The White Album: two albums, thirty wildly diverse songs.

KRISTY KRUGER: I thought it was the most amazing piece of music I had ever heard.

JON SPURNEY: I thought it was about the weirdest album I’d ever heard: amazing melodies that are impossible to forget.

SUZANNE KRYDER: It was like, what happened to the Beatles? It was just scary, like “Glass Onion.”

INGLES: Today, Beatles fans and musicians gather to experience The White Album again. Stay tuned for The White Album Listening Party.

HOUR ONE

INGLES: Hi. I’m Paul Ingles. Around Thanksgiving, 1968, I was twelve and one of the millions who went out to buy an extraordinary new collection of songs from the Beatles: John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. Since Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in 1967, there hadn’t been a full album of Beatles material. Magical Mystery Tour and Yellow Submarine both mixed a few new tunes with previously released singles and “B” sides, but now, a double album, in an era when double albums weren’t often done. In contrast to the psychedelic covers of their previous, three albums, this jacket was all-white, the words, “The Beatles,” embossed at an angle, in small print on the cover. The music inside was, frankly, bizarre to me, but a stimulating mix. I remember feeling, after a first listen in the wood-paneled basement of my family’s home in suburban Maryland that this wasn’t an album that we could play on the family stereo, upstairs, because a lot of it seemed, well, either naughty, tortured or just edgy. I used to listen with my best friend, Johnny Sedwitz. Johnny Sedwitz is not here with me today, but I am here with other friends. We’re going to hang out and listen to The White Album again, and remember, with you, what it was like to hear it for the first time.

PARKIN: My name is Travis Parkin. I was 19 years old in 1968.

KRYDER: I’m Suzanne Kryder. I was 13 in 1968.

MacNICHOLL: I’m Scott MacNicholl. I was just turning 15 when The White Album came out. I was living here, in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

URBANO: I’m Luciano Urbano. I was 14 in 1968. I grew up in west Texas.

PARKIN: I was rooming with some college students from the University of Michigan, near the campus. I was listening to it in a guest room they had upstairs.

KRYDER: I suspect that I didn’t listen to the whole album until a couple of years later, probably in Bill Barrington’s basement.

MacNICHOLL: My distinct memory is the first listen with about eight or ten of us. We sat quietly – for teenagers – on a Sunday afternoon, and listened to all four sides, straight through.

URBANO: I was a migrant worker in those days. We couldn’t afford stereos, and we couldn’t afford LPs, but we heard about it. Radio, at that time, was being adventurous, so we got to hear some Beatles’ music that we could not hear on regular radio.

INGLES: We also have a panel of musicians, both here and across the country, to help tune our ears to the musicianship of the Beatles.

SPURNEY: Hi, My name’s John Spurney. I’m a musician and composer in New York City. I was three years old, when The White Album came out, so the first time I actually heard it was in 1978, when I was 13. I heard it at my family’s beach house in Rehobeth Beach, Delaware. I thought it was just about the weirdest album I’d ever heard.

KRUGER: My name is Kristy Kruger. I’m a singer-songwriter in Dallas, Texas. I was not born in 1968. I first listened to The White Album in 1996, when I was 19 years old. I had taken a Beatles course at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. I thought it was the most amazing piece of music I had ever heard.

GRANT: This is Douglas Grant. I’m a musician, recording engineer and producer in Tucson, Arizona. I lived in the U. K. in 1967 and ’68, and had just returned to Vermont. So I most certainly heard it on the console, furniture stereo in the living room, which wasn’t too exceptional, because my mother used to buy us the Beatle records, as they came out. This one, certainly, was not likely to please her musical ear nearly as much as previous ones had.

GANS: My name is David Gans. I’m in Oakland, California. My parents were liberals, so they didn’t mind us playing that weird stuff on the cheap stereo in the living room. I think I was in the tenth grade, when The White Album came out. Less than a year later, I started playing the guitar. The two songbooks that I used to teach myself cords and stuff were the CSN songbook and The White Album songbook.

MARTINEZ: I’m Rob Martinez and I live in Albuquerque, New Mexico. I’m a singer songwriter. I play in a ‘50s rock band called The Daddy-Os. In 1968, I was five years old. It would be ten years before I would get into the album, 1978. My buddy, Andrew Alfelder, and I would learn these songs in our high school band. While everybody else was learning Van Halen and AC/DC, we were knocking out “Happiness Is a Warm Gun.”

INGLES: We’re going to give a close listen to The White Album. To help us understand where these tunes came from, we have, on the line from London, our friend, Steve Turner, author of the book, A Hard Day’s Write: The Stories Behind All the Beatles’ Songs. Steve, we’re going to start by tracking cuts one and two on Side One: “Back in the USSR” and “Dear Prudence.” What can you tell us about these two?

TURNER: “Back in the USSR” was mainly a Paul song. The whole thing about The White Album is that a huge percentage of the songs were written when they were in India. It was really the last time that all four Beatles were together and had leisure time, had time to sit around and play songs to each other in a relaxed environment. Mike Love of the Beach Boys was there, as was Donovan. Mike Love said to Paul, “wouldn’t it be great to do a song about the Soviet Union, in the style of Chuck Berry’s ‘Back in the USA?’” So Paul started this song. It was a pastiche of Beach Boys and Chuck Berry, extolling the virtues of the Soviet Union, rather than the USA. That was the whole joke of it. Of course, when it came out, there were already some people who were suspicious of the Beatles, and their possible leftward leaning, who thought this was terrible, that they would sing a song in praise of the USSR. They didn’t get the joke, at all.

MARTINEZ: It was also indicative of some of the problems the Beatles were having at the time. I think Paul’s playing lead guitar. I think he was playing drums, because Ringo wasn’t in the studio at the time. I think he was angry or something.

GANS: I heard that there was this sense of competition between the Beatles and the Beach Boys, that each was trying to top the other, or worried that the other guy was doing better work, or something. What an amazing thing, if Brian Wilson and the Beatles were spurring each other on to greater heights. It feels like this song is both a brilliant parody of American rock and roll and also a nice salute to the Beach Boys.

SPURNEY: On the bridge, those high “whoo-whoo-whoo's,” the fact that the idea was suggested by Mike Love. It makes total sense, when you listen to it.

INGLES: What about "Dear Prudence"?

TURNER: “Dear Prudence” was also written at the meditation academy. It’s about Mia Farrow’s sister, whose name is Prudence. She got into the meditation almost too heavily, at first. She’d done too much meditation and had gone into a trance like state and was staying in her bungalow longer than she really should. John wrote this song that said, “Hey! Come out! Enjoy life!” It’s a very personal song, addressed to her.

SPURNEY: “Dear Prudence” is probably my favorite song on The White Album. It features this really beautiful, finger picking guitar by Lennon. My understanding is that, when they were in India, Donovan taught Lennon some rudimentary finger picking patterns: playing the guitar with individual fingers, rather than using a pick.

KRUGER: When I listen to “Dear Prudence,” I feel that song does, in terms of production, everything that a good book should. It starts with a very sparse instrumentation: mostly guitar. You get a little hint of bass. You get a little hint of, I think, a bass drum. I guess it’s Paul, playing drums. I think it’s absolutely genius, how he lays out and when he comes in, it’s just bass, bass snare; bass, bass snare. At the end of the song, he lets loose, like a lion who’s been let out of his cage. I love the growth the song has, from beginning to end. I really feel there’s a climax, a denouement, and the song sort of fades out.

SPURNEY: The bass line has this beautiful counter melody, with glisses on the bass. He’s sliding between the notes, rather than playing the notes individually.

KRUGER: I felt it was a beautiful example of how the Beatles used their background vocals to provide a film score for the lyrics that are presented to you. The first introduction of the background vocals is at the word, “sky.” They’re holding the notes for a long time; it sort of feels like an opening in the sky. When he sings, “look around,” you hear the background vocals, singing, “’round, ‘round, ‘round.’” Sonically, it provides a circular motion.

GANS: That’s one of the hallmarks of latter day Beatles stuff: how amazingly they use their voices as orchestration.

KRISTY: Yeah.

INGLES: You guys are doing great. I’m going to jump in, ‘cause we’ve got 28 more to go.

“Back in the U.S.S.R.” and “Dear Prudence” play

INGLES: You’re tuned in to The White Album Listening Party. I’m Paul Ingles with our many guests, re-experiencing the Beatles’ White Album, released in 1968. Next on Side One, “Glass Onion. And then, “Ob-Lla-Di, Ob-La-Da.” To London and Steve Turner. What about these two, Steve?

TURNER: Part of what prompted

“Glass Onion” was a letter that John was sent, by a pupil at his old school

in Liverpool. I think it was part of an English lesson, or something. He’d written

and said, “Could you tell us how you write your songs, and what the meanings

are?” A few years ago, I found out this guy’s name is Steve Baley. He’s sort

of a design guru now. Anyway, he wrote this letter to John. John wrote quite

a nice letter, back. It said, “People attach all these meanings to songs that

I never intended, in the first place.” Then he thought he’d actually write a

song – the complete trail of red herrings, basically: images that would lead

people into speculation. He either made them up, randomly, or some of them had

origins in real places or incidences. “The cast iron shore” is an example: it’s

a beach on the River Mersey in Liverpool. “The bent-back tulips:” Doug Taylor

told me there was a restaurant in Knights Bridge called Parks. The owner had

tulips on each table. He used to actually bend the petals back. So, that image

came from that. But they’re basically grabbed out of the air, to confuse people.

“Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” that’s a Paul song. He certainly started that in Rishikesh,

in India. It was based on a phrase from a guy called Jimmy Scott, a conga player

from Nigeria. He’d been using this phrase quite a lot. He’d shout out, Ob-La-Di!”

and the crowd would shout back, “Ob-La-Da!” Then, he would say, “Life goes on!”

He actually had a band called the Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Di Band. Paul loved the phrase,

built a song around it and gave it a kind of Jamaican, reggae, ska beat. Jimmy

Scott got in touch with him, after it came out and demanded money. Some sort

of financial resolution was made.

INGLES: David Gans, what do you like about "Glass Onion"?

GANS: “Glass Onion!” It has the same sort of feeling as an overture quality, that the beginning of Sgt. Pepper had. It’s self referential, in a funny way. The other thing I love about it is the string glisses: with the orchestration, there’s this rubbery string section. When I listen to this – and the rest of this album -- I think this is where Jeff Lynne got the idea for the Electric Light Orchestra.

INGLES: John?

SPURNEY: The first time I heard “Glass Onion,” as a kid – not as a musician – the whole self-referential lyric thing, the idea of writing a song that’s ultimately about songs that you’ve written before, to me was a mind-blowing thing. To listen to the song you, basically, have to be in the club. You have to know the songs that have come before it to appreciate the references that are made. There are even sly, musical references. Like, after he mentions “the fool on the hill,” there’s a recorder, playing a version of the line that the recorders play on the actual record, “The Fool on the Hill.” That whole self-referentiality was a new thing. When I was a kid, it really struck me.

INGLES: It was an acknowledgment of their legacy, for the first time, I thought. “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” John Spurney?

SPURNEY: If you read about the recording of the record, they had been through, literally, hundreds of takes. There’s a previous version, that I think is on the Anthology that you can hear, that’ s arranged very differently. It revolves around acoustic guitar. When they got around to the arrangement that wound up in The White Album, Lennon was playing the piano. The introduction, if you listen to it, is played really hard on the piano. Supposedly, that’s because Lennon was so angry that they were doing the 150th take. On the master tape, there’s an expletive before they started playing, because he was so sick of playing it over and over. But the thing I love in the song is the saxophone chart that George Martin wrote. There’s a beautiful, counterpoint melody that the saxophones play.

GRANT: I’m glad you brought up George Martin’s horn charts there, because there are a number of places on this album where he makes an incredible contribution to this album.

GANS: One more thing, before you drop “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” the maracas. God, the maracas! One of the coolest things about Beatle records is how spare the percussion is and how amazing their grooves are, without huge numbers of drums and cymbals in use.

“Glass Onion” and “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” play

MacNICHOLL: It all seems like this is a troupe of actors, mimes and musicians. This whole thing comes out in a childlike, “Romper Room” ditty. I see people with colorful makeup on, dancing around as they sing this song.

INGLES: I liked the song, for a while. But I stopped liking it after about ten years or so. I can hardly stand to listen to it, any more. Suzanne?

KRYDER: Where’s “I Want to Hold Your Hand?” What happened to the Beatles? I wasn’t into the musicality of the album, because I was such a young kid. But it was just scary. Like, “Glass Onion:” it was too much to try to figure out where they were coming from. I just wanted the old Beatles back.

PARKIN: “Glass Onion” was a confrontational song. John was confronting his fans and listeners with their rumors. It showed what a conscious guy he was. How many people would make a song about their songs, and about their relationships with their fans?

URBANO: “Glass Onion,” in those days – in the ‘60s in west Texas – we weren’t aware of. But “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” right away brings a big ol’ smile to me. Working in the fields – in those days, a hoe was a tool that we cut weeds with. We’d dance with those hoes. We played guitar with those hoes. We’d sing “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da!” We were American; we were Mexican-American, and I remember singing and dancing with those hoes and playing the guitar. That was the American side of us.

INGLES: I could see how that could be a “whistle while you work” type song, for sure. One of George Harrison’s greatest, just ahead on our White Album Listening Party, so stay tuned.

“Wild Honey Pie” and "The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill” play

INGLES: The Abbey Road crowd applauds cut six on Side One of the Beatles’ White Album. That’s “The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill.” Kristy Kruger?

KRUGER: I love all the kids and all the voices: all the characters singing. I feel it’s the introduction of all these character voices. They’re not singing as voices, singing songs; they’re little characters. I love how the melody modulates from major to minor. They do an interesting tonality shift. The melody starts in atonic and the tonal center moves a minor third down, but shifts to major. I love the way they decided to end this song. I feel this started happening more often, where the song doesn’t have a clear end. I don’t want to say it collapses, but it starts to slowly, organically fall apart. There’s disheveled whistling, almost like a car where the hub cap falls off, the license plate falls off, and it just slowly happens.

SPURNEY: It’s got the singing debut of Yoko on a Beatles’ record: the “when he looks so fierce” line.

KRUGER: I thought it was a creative piece of music. I wasn’t around in 1968. It still sounds surprising and creative to me today, in 2008. I can’t imagine what it sounded like then.

INGLES: You’re listening to “The White Album Listening Party. Next up, George Harrison’s “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” and then, John Lennon’s “Happiness Is a Warm Gun.” Steve Turner, I read in your book that each one of these songs was born when each writer’s eye was drawn to a phrase on a printed page. Is that right?

TURNER: Yes. “Happiness Is a Warm Gun” and “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” would be connected in that sense. They each came from a random sighting of words on a page. In George’s case, he was into I Ching and the idea of randomness. He just picked a book, off a shelf in his mother’s home, opened it at a certain page, saw this phrase, “gently weeps,” and built a song around that phrase. “Happiness Is a Warm Gun” is a phrase taken from an advert in a magazine that caught John’s eye – I think it belonged to George Martin – it was lying around in the studio. It was based on Charles Schulz’ “Happiness is a warm puppy.” John liked the fact that it had “happiness” and “gun” in the same phrase; he thought that was a strange thing to use. The song is actually made up of three, different songs that were started, but not finished. That became a technique they used quite a bit: actually using two or three. Well, “A Day In The Life:” that used two or three unfinished songs, and jammed them together.

SPURNEY: I just love the structure of it. By that, I mean that it has no structure. Most pop songs are A, B, A, B, C, A, B. “Happiness Is a Warm Gun” is A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H. There are disparate sections that really aren’t connected to each other, musically or lyrically. It’s a bizarre pastiche of loose ends. Together, they’re definitely greater than the sum of their parts.

MARTINEZ: You also have an amazing piece in the middle, the “Mother Superior jumped the gun” part. It has an odd time signature. Lennon was really good at that. I don’t know if he meant to be. I remember reading somewhere that Ringo Starr said that Lennon had terrible timing. So, sometimes, he would just play these weird, off-beat time signatures, like you hear on “All You Need Is Love.” But boy, they really work.

GANS: In the last section, it shifts into 3/4. I wonder, given what Rob was just saying, if that was intentional or inadvertent.

INGLES: Rob Martinez, start us off on “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.”

MARTINEZ: This is, obviously, the centerpiece contribution to the White Album by George Harrison. There’s a version out there – I think it’s on the Anthology or on “Love” – the acoustic, demo version of the song is really haunting and beautiful. I love listening to that. But this version has McCartney on piano, Eric Clapton on lead guitar. Apparently, Eric Clapton was brought into the studio because, at this time, the Beatles were being “quite bitchy,” as George Harrison used to say, with each other. So he thought, if he brought an outsider in, everyone would behave themselves. True enough, when Eric Clapton came into the studios, everyone behaved himself, and played a pretty good version of this song. The song has a certain, heavy metal quality about it, almost getting us ready for the ‘70s: a big, huge, arena rock-type sound.

“While My Guitar Gently Weeps” and “Happiness Is a Warm Gun” play

INGLES: The White Album, Side One ending with “Happiness Is a Warm Gun” and “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” before it. What comes to mind, Suzanne?

KRYDER: So much of my relationship with this album was about each of the guys. George was the shy Beatle, that girls wanted to take care of. You loved his voice and loved the song; it was so powerful. But John was the creepy Beatle; there was just something wrong with him. As a kid, I didn’t know what depression was; I just knew that this guy was really depressed. The song was just so scary. A friend of mine told me that it wasn’t really about sex. It was about shooting up heroin. It was really creepy.

MacNICHOLL: When you hear things like “Happiness Is a Warm Gun,” you hear a bit of their ripple effect, coming back to them from the rest of the music world: grungy guitars and stuff, where they had been so produced. And here, you have a more raw, rock and roll sound, as opposed to the more produced things you’d heard recently, in Magical Mystery Tour and Sgt. Pepper.

INGLES: I think George Martin even left the sessions, for three months or something, and turned it over to Chris Thomas because, I guess on many tracks, he wasn’t being called on to do many orchestrations or some of the things he’d been asked to do in the past.

This is “The White Album Listening Party:” about a dozen Beatle fans and musicians, hanging out in our virtual basement here, re-experiencing the Beatles’ 1968 collection of songs known as the White Album. I’m Paul Ingles. Side Two starts with a jaunty, Paul McCartney tune and then a languid John Lennon tune: “Martha, My Dear,” then “I’m So Tired.” Steve Turner is the author of A Hard Day’s Write; he’s on the line with us from London. Steve, what can you tell us about these two songs?

TURNER: “Martha, My Dear,” I think, grew out of a Paul piano exercise – technically, that’s where it grew from. But he did have an old, English sheep dog called Martha. That gave the title. It wasn’t a real girl. It’s certainly not a song about a dog, but that’s where the name, “Martha,” came from. “I’m So Tired” is a John song, written out in Rishikesh. Mind you, he had written quite a few songs that alluded to tiredness, in some way. He seemed to have liked his bed, in that way. But I think, when they were out in Rishikesh, meditating for, sometimes, six or seven hours on end – and the fact that they’d escaped the show biz world of London – I think there was a kind of arrestedness, more than a tiredness, but that’s John, talking about Rishikesh.

INGLES: Kristy Kruger, “I’m So Tired” is a favorite of yours, I hear.

KRUGER: I would actually say it’s my favorite song, ever, if I had to pick one song and listen to it on “repeat.” “I’m So Tired” fuses two, different styles. One is a ‘50s pop ballad style. It reminds me of “Earth Angel” a little bit. I love the way he pleas. He’s shouting out to someone, “I’d give you everything I’ve got for a little peace of mind.". Then he just lets that sentiment linger in the air. Then they shift from this ‘50s pop feeling to a blues – a grinder sort of sound.

INGLES: This is an example of where, a couple of times, at least on this album, Lennon does let loose, vocally. Douglas Grant, you had something to say about “Martha, My Dear.”

GRANT: “Martha, My Dear” is real, essential Paul McCartney’s extremely strong, melodic gifts, coupled with lyrics that are – shall we say? – not quite as deep as George Harrison and John Lennon were penning at the time. I don’t think he’s real comfortable with the bare-your-soul approach that George, in a spiritual way and John, with self-revealing tendencies, would do. He certainly made up for it with amazing melodies that are just impossible to forget: great middle arrangements, with horns and strings. It’s just a very well constructed song and recording.

SPURNEY: McCartney has this knack for coming up with these riffs that, when you play them and figure them out, aren’t difficult to play, but they’re just strange. They’re counter-intuitive. They’re instantly accessible.

MARTINEZ: That first line, “Martha, my dear,” the intervals get you, right away, and then he just doesn’t let go of you. This is just another fun song that makes you feel the sun is shining, when you listen to it.

“Martha, My Dear” and “I’m So Tired.” play

INGLES: That’s “I’m So Tired” and “Martha, My Dear,” the first two tracks on Side Two of the four-sided, 1968 release by the Beatles that came to be known as the White Album. We have lots more to hear, obviously, and, when we reconvene, we’ll have more from our gang we have here, hanging out, listening. That would be Scott MacNicholl, Luciano Urbano, Travis Parkin, Suzanne Kryder, Rob Martinez, John Spurney, Kristy Kruger, Douglas Grant, David Gans and Beatle author, Steve Turner. My thanks also to John Oswick. Our engineer is Roman Garcia, helping us in the studios of KUNM in Albuquerque. I’m Paul Ingles. I hope you can join us for the next hour of “The White Album Listening Party.”

INTRO TO HOUR TWO

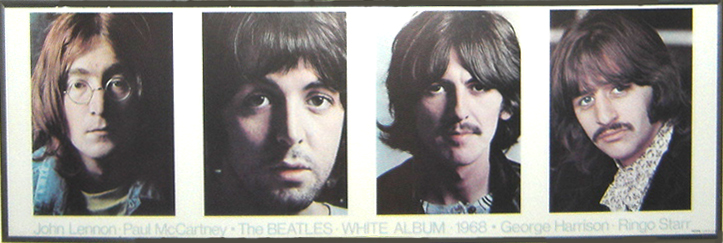

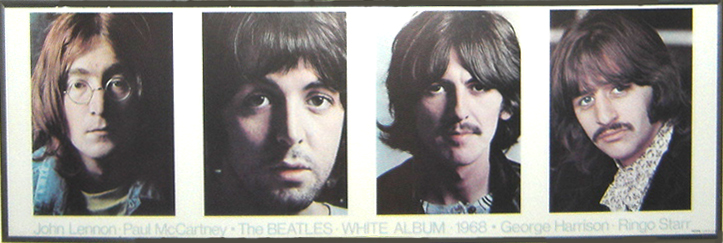

INGLES: In 1968, the Beatles entered what many consider the last of three phases of their career as a band. They had been the lovable "Mop Tops." Then, they were the psychedelic "Mystery Tour" guys. Then, with 1968's The Beatles, also known as the "White Album," John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr were beginning to head in the four directions that would result in the band's split, in a little over a year.

GANS: They were each discovering their own, individual voices. This was the moment of their differentiation.

KRYDER: Where's the Mop Tops? I just wanted them to cut their hair and get the matching suits on again.

INGLES: Today, Beatles fans and musicians gather to experience the White Album again. Stay tuned for Hour Two of "The White Album Listening Party."

HOUR TWO

Hi, I'm Paul Ingles. Welcome to the second hour of "The White Album Listening Party," to mark the 1968 release of the Beatles' diverse, double-album collection of songs. We've assembled a gang of radio personalities and musicians to hang out in the studio here, and elsewhere around the country to listen, track-by-track, to what came to be known as the Beatles' "White Album." Let me tell you who we have here: Scott MacNicholl, Luciano Urbano, Travis Parkin, Suzanne Kryder and Rob Martinez are here at our studios in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Around the country, John Spurney, Kristy Kruger, Douglas Grant and David Gans. Last hour, we had just started Side Two. We pick up with cuts three and four on Side Two: "Blackbird," by Paul McCartney, followed by "Piggies," written by George Harrison. We're also happy to have with us on the phone from London Steve Turner, author of A Hard Day's Write: The Stories Behind All The Beatles' Songs. Steve, what can you tell us about these two?

TURNER: "Blackbird" was written by Paul. He says the tune came from a classical tune from a teach-yourself songbook that he and George had, when they were teenagers. It's hard to actually detect that influence. I think what Paul's meaning is that, by trying to play this classical piece and altering it a bit, he came up with this beautiful, new tune. I think it also, lyrically, alluded to what was going on in America at the time: the assassination of Martin Luther King and the race riots in America. It was a song of encouragement to the African American community. "Piggies" is a George song. I think it was meant semi-humorously. It was an attack on the bourgeoisie, calling them pigs in the same way Orwell used the pigs to refer to the ruling class in Animal Farm. Unfortunately, it is one of those songs that Charles Manson took a little bit too literally. When George sings about the knives and forks and attacking the piggies, Manson took that seriously. In fact, they scrawled "Piggies" in blood at some of the sights of the Manson family murders.

INGLES: Harrison was, of course, horrified when he heard that, I'm sure.

TURNER: Absolutely.

INGLES: Anyone else on "Piggies?"

MARTINEZ: It's definitely not characteristic of George Harrison, and that's why I like it. It's sonically more like McCartney, with harpsichords and cellos. It's a baroque-sounding piece of music, except the part where the piano goes into a little blues-like thing, thrown in, which I love. Then, that last flourish with the strings, where George says, "one more time:" to me, that sounds like ELO, Electric Light Orchestra, which will be coming next year or something like that.

SPURNEY: One thing that has to be said about the White Album is that there are a lot of sound effects on it. "Back in the USSR" has the airplane. "Piggies," obviously, has the sound of pigs. "Blackbird" has the sound of a bird. It's throughout the entire album. You could argue that "Revolution #9" is, essentially, only sound effects.

KRUGER: Lyrically, I thought "Piggies" was rich, taking a critical look. You can see them, out for dinner with their piggy wives, clutching forks and knives to eat the bacon.

MARTINEZ: Cannibalistic.

KRUGER: Yeah. It's very poignant, actually.

INGLES: It has a little "Tax Man" flavor.

KRUGER: Yeah, so much the objector voice coming out.

GANS: "Piggies" does verge on self-righteousness, too.

KRUGER: Yeah. I think every one of us has had that feeling, at some point: that you've been in the presence of the piggies.

INGLES: Kristy Kruger, why don't you start us off on "Blackbird"?

KRUGER: "Blackbird" is an absolutely timeless piece of music; in the way that Bach or Beethoven is timeless. It is this simple, beautiful melody. The production is so simplistic. The only change that we really hear is that, in the "B" section, Paul doubles his vocal. Other than that, all we hear is just the guitar and his foot, tapping. It's one of those pieces of music that is so rich, harmonically, yet it's so easy to execute. A beginner could execute that guitar part. I think that's why every beginner, learning to play guitar, one of the first songs they learn is "Blackbird."

SPURNEY: Again, it has that incredible simplicity that McCartney is so gifted at, where it's not difficult, physically, to play, at all. But, when you take it apart as a musician, it's very easy to put your fingers where you need to put them to play it. But, when you're playing it, you're thinking, "Why would anyone have ever thought to put their fingers here?

KRUGER: I think it will be around for centuries. I think it's timeless.

GRANT: Lyrically, it's one of Paul's most poetic, as well.

"Blackbird" and "Piggies" play

INGLES: "Piggies" and "Blackbird." I'll start us off by saying that "Piggies" sure sounded menacing to me back then: a song that had "damn" in it, "a damn good whacking" seemed illicit to a twelve-year-old. Anyone else on these songs?

KRYDER: 1968 was a pivotal year in my life. I was in the 7th grade, which was elementary school. Martin Luther King was assassinated. I remember my parents didn't get real upset about it. Their reaction was this creepy blend of fear - is it going to be worse now? - and some relief. I remember that I was just devastated when Bobby Kennedy was assassinated. What I learned from those two murders was that people who speak up get killed. That fall, I went to high school, in the 8th grade. A song like "Piggies" was just terrifying to me. I didn't even listen to the words. All the - what I would call - "Satanic" sounding songs on the album were really scary. It's not that any of it made any sense. It's that the White Album seemed to reinforce the scary world syndrome.

INGLES: Moving on with Side Two, here comes "Rocky Raccoon," "Don't Pass Me By," and "Why Don't We Do It In the Road." Beatle author, Steve Turner, what's the headline on where these songs came from?

TURNER: "Rocky Raccoon" was Paul's song. It was written out in Rishikesh. When they were in India, strangely enough, their minds turned back to Liverpool and childhood. "Rocky Raccoon's" a cowboy song. It shows Paul's inventiveness: his ability to create characters and stories, which he was always very good at. John wasn't as good at doing that. John would deal more with emotion and feeling. Paul avoided emotion and feeling, really, and tended to make up stories.

GANS: All I can say about "Rocky Raccoon" is that the tack piano is fabulous.

INGLES: Which was played by George Martin.

SPURNEY: But it was recorded at half speed, just like the piano solo on "In My Life," which is another, beautiful, piano solo, played by George Martin. It was also recorded at half speed. That enables the musician to play the part more slowly, which is easier, but also changes the timbre of the instrument, when played back at regular speed. That's a big part of "Rocky Raccoon:" that instantly evocative saloon piano sound. It's one of my favorite things on that song.

KRUGER: His really bad, fake, Southern accent is also to be noted.

INGLES: Yeah, that always made me laugh. Again, I'm giving the twelve-year-old's perspective. It was a stunt, for us to be able to sing back those lyrics. "Somewhere in the black mountain hills of Dakota, there lived a young boy named Rocky Raccoon." We all tried to see how far we could get.

MARTINEZ: I still can't get that right. I still mess that up.

GANS: Jamming all those syllables into that short space.

INGLES: "Don't Pass Me By:" Ringo's star turn.

TURNER: When I was listening to some old radio interviews the Beatles did from the '60s, there's one from 1964 in Australia, where Ringo is shouting in the background about a new song he's written. It's "Don't Pass Me By." Then, Paul's saying, "Oh, I don't know if we're going to put it on the next album. Well, that just shows you how long that song had been knocking around: five years, before it actually got released on an album.

GRANT: "Don't Pass Me By" has always struck me as a reprise or tip of the hat to Ringo's cover of Buck Owens's "Act Naturally." It's got a fiddle in it and a country arrangement.

MARTINEZ: It's country-ish: "Because I love only you."

KRUGER: I think it begs for a country arrangement. That's definitely not my favorite on the album. I was playing a bar somewhere. Somebody walked by and started singing it. When I heard the melody, on its own, I heard it in a totally different way. "Don't pass me by. Don't make me cry. Don't make me blue."

MARTINEZ: It's a great melody.

INGLES: Excellent. Add that to the set, Kristy.

KRUGER: Actually, at one point, I did. But I can't remember how it goes. The lyrics start out, but then they get really weird or something.

INGLES: You were in a car crash and lost your hair and . . .

KRUGER: Then, I thought, "yeah, I don't know." What is that instrument that goes throughout the whole song that sort of gives me a headache?

GRANT: There's a Leslie piano, playing on it.

MARTINEZ: Leslie, yeah.

KRUGER: It's just really obnoxious and hard to listen to.

INGLES: "Why Don't We Do It In the Road?"

TURNER: It's a Paul song: a complete contrast to what you expect of Paul, if you think he can only write "Yesterday." It's a loud, attacking, primal song, written in Rishikesh. He saw the monkeys out there, mating, and thought, "Why aren't we like the monkeys? Why do we attach such shame to making love, whereas the animals don't?" That was his reasoning behind the song. It sounds like a very trivial question, but it could be the most profound. Why don't we behave like animals?

INGLES: Kristy?

KRUGER: I love it. First of all, lyrically, I love the sentiment. It's so simple. "Why don't we do it in the road? No one will be watching us. Why don't we do it in the road?" There are no other lyrics in the entire song. I love the fact that the song sounds like doing it in the road. He has used dirty blues to score his desire here. I also love how, vocally, toward the end, he's heading toward what I would deem a climax. It sounds like he's getting close to that, toward the end of the song. I think it's bold. It's a bold suggestion. It's something I would love my lover to say to me. It's open, love, right out there. It's a big statement of freedom. It sounds like doing it in the road.

GANS: Ok, note that, guys. Kristy prefers the direct approach.

MARTINEZ: Duly noted.

INGLES: This is all McCartney, by the way, every part of it.

SPURNEY: As is "Wild Honey Pie." As long as we're talking about songs we don't like, . . .

MARTINEZ: I don't like "Wild Honey Pie."

SPURNEY: Yeah. And I don't like "Why Don't We Do It In the Road." There were a lot of songs on the White Album that, when they were assembling the album, they had recorded all these songs and George Martin begged them to make it a single disc, rather than a two disc, album. I personally feel there are a lot of songs on the record - even as much as I love the Beatles and as unassailably great as they are - I really think of as filler. It's an interesting party game to sit down and say, "If you were going to make the White Album,"

MARTINEZ: "Which would you keep and . . ."

SPURNEY: "If it was just going to be on disc."

MARTINEZ: The White Album, I think, was at the height of their egos really being out of hand. That comes across because you do get stuff on there that, maybe if it was a record company today putting out that record, they wouldn't have those songs.

GANS: The other way of saying that is that they were each discovering their own, individual voices, and this was the moment of their differentiation.

SPURNEY: A really strange thing about the White Album is that you have a situation where the Beatles are almost acting as sidemen for whoever wrote the song. The strongest voice that you hear in an individual song is that of the writer. Everybody else is there, doing whatever the writer tells them to do.

MARTINEZ: Exactly.

"Rocky Raccoon," "Don't Pass Me By" and "Why Don't We Do It In The Road" play.

INGLES: "Why Don't We Do It in the Road," "Don't Pass Me By" and "Rocky Raccoon." Scott?

MacNICHOLL: "Rocky Raccoon." An episode of "Gunsmoke," put to song. What really rings in my head is underground FM, when I was just being introduced to it. This song was the one they really seemed to pick up on.

INGLES: That's something worth mentioning, because in 1968, this album was so deep. It had so many songs. If it were more the era of hit radio on AM that we were depending on up until 1966 and 1967, we wouldn't have heard very many of these songs. Whatever they might have picked for a single, we might have heard just a couple of tunes. But, because of FM radio, the DJs, who were given free reign, were really digging deep and playing just about everything from start to finish. Travis?

PARKIN: The other thing I wanted to mention about the song, "Don't Pass Me By" had a beautiful, bluegrass fiddle. My parents were big Hank Williams, Patsy Cline people. As kids, in our late teens, it was totally uncool to listen to country music. But, when this fiddle came in, I had to rethink my position.

KRYDER: These three cuts really epitomize to me how I just couldn't get this album. As an adult, I love it. I really respect all the music and enjoy it. But as a kid, I thought, "These guys are so freaked out on drugs! It's so crazy!" All these songs were so different. You've got crossover to country, a song my grandparents would love and then this incredibly lascivious - you know, I've seen monkeys, copulating in India - it was upsetting. I thought I'd lost them.

INGLES: OK, Suz, we'll see if they can reclaim your love with the two, acoustic gems that close out Side Two. We'll hear those next. I'm Paul Ingles. You're listening to "The White Album Listening Party. More after this break.

You're tuned to "The White Album Listening Party," a celebration of the 1968 release of the Beatles' double album, landmark recording. It came to be known as the "White Album" for its unadorned, all-white cover. I'm Paul Ingles, along with a host of others, both here, in our Albuquerque studios and around the country. We're listening to the "White Album" track-by-track to see what memories and stories come up. For the stories behind the songs, we're going to author, Steve Turner, who, literally, wrote the book on that. It's called A Hard Day's Write. Steve, we close Side Two with two acoustic numbers: "I Will," from Paul McCartney, and "Julia," by John Lennon. What can you tell us about this pair?

TURNER: There's a similarity, in that they're both songs - one written by John and one by Paul - about the most important women in their lives. I think "I Will" was about Linda. Linda Eastman came into McCartney's life shortly after their stay in Rishikesh. In fact, she was in the studio for some of the recording for the White Album. "Julia" was written by John about his mother who was, certainly, the most important woman in his life.

INGLES: Julia, John's mom had left John to be raised by an aunt.

TURNER: That's right. John was living at home with his aunt, Mimi, and Julia was living not too far away. Julia would come over, periodically, to see John. She'd come over this one day and John wasn't in, for some reason. She left the house, crossed the road, was hit by a car and killed. I think John was about 17 or 18, at the time. It was a terrible blow to John. You can attribute a lot of John's bitterness and misogyny, I think, to that. Maybe he never would have become the songwriter he became, if that hadn't have happened. The first, two lines of "Julia" are taken from a poem by Kahlil Ghibran, almost word-for-word.

INGLES: Rob?

MARTINEZ: I love the song, "Julia." I think it shows a vulnerability. It shows a side of John that's very romantic. The part I love the most on the vocals is, "So I sing this song of love." It's heart rending. His voice is double tracked. It always makes me think of John Lennon and remember him.

SPURNEY: It's a really nice texture because it's finger picked. It's the same pattern as "Dear Prudence." It's double tracked: once, on the acoustic and once on an electric. Those two timbres mixed together beautifully.

INGLES: Rob Martinez, why don't you start us off?

MARTINEZ: "I Will" is one of those perfect, Paul McCartney ballads. For me, one of the most fascinating things is that, I believe, the bass line is Paul's voice.

SPURNEY: Yeah. The bass is totally accapella. It's beautiful.

KRUGER: I heard that today when I was listening to it. I was thinking, "Is somebody singing that bass part?" I'd never noticed that before.

MARTINEZ: What a cool idea! I'm going to do that on one of my songs, if I ever write a song that good.

KRUGER: The melody here is one of those dreamy melodies that reminds me of the 1930s and 1940s. You feel like there's bluebirds in the air. It's one of those romantic, heady melodies.

GANS: I remember, distinctly, the radio commercial for the album. It included a snip of that: "If you want me to, I will." It's such an absolutely stunning, melodic phrase.

KRUGER: You can see some girl, swirling around in a beautiful dress on a stage. It's timeless.

"I Will" and "Julia" play.

INGLES: There's "Julia" and, before that, "I Will," closing out Side Two, Record One of the Beatles' White Album.

MacNICHOLL: They almost sound as one. As we listen to them there, back-to-back, it seems they were paired that way on purpose. They're very similar, in my head, in their pacing and the way they're played. It's very simple, very straightforward and very pretty songs.

KRYDER: "I Will" sounds like a Beatles song. It reminds me of the old Beatles - maybe something off of "Rubber Soul." I really love that song.

INGLES: Travis?

PARKIN: It was the spring of 1969. It was a beautiful, Saturday morning. One of my temporary roommates gave me a tab of "windowpane" that morning.

INGLES: For the uninitiated, that is a tab of acid. Is that right?

PARKIN: Right. It looked like a tiny chip of…

MacNICHOLL: plastic…

PARKIN: …microfilm or plastic. It was, usually, a purple color.

MacNICHOLL: There you go!

PARKIN: Yeah.

KRYDER: God I missed so much, you guys. Oh, man.

PARKIN: And I ingested it. Probably an hour and a half, two hours, later, I was walking through the beautiful streets - which were a little wobbly, at the time - of Ann Arbor. I heard this song, "Julia." It seemed like it was coming from miles away. It was drawing me, like a siren - in the Greek, mythological sense. It seemed like it took a week for me to get to the source of that song. When I got where it was coming from, it was a garage sale. The semester was over. One of the students was packing up. He had all of his albums out there. This was the album he was playing. That was the second Beatles' song I became familiar with, after "Rocky Raccoon." It was "Julia." I just loved it. To this day, I have an affinity for the name Julia, as a result.

INGLES: We're going to get into Side Three now. It starts with the rockers, "Birthday" and "Yer Blues." Steve Turner, what about these two?

TURNER: Paul wanted to do a song in emulation of a song called, "Happy, Happy Birthday," a rock and roll song of the '50s.He wanted to do a celebratory birthday song that was hard rock. "Your Blues" is John, mocking the blues idiom while singing a blues song. He was going through a tough time - again, written out in India. His relationship with Cynthia was coming to an end. Yoko was on the scene, writing him letters. He was in turmoil. He was wanting to be with Yoko, but he was with Cynthia. He didn't know what the honorable thing to do was. "Yer Blues" was about that. Also, it was the time of the British blues boom, in the late '60s, in Britain. There were always arguments, in the British papers, about "Could white people, authentically, sing the blues?"

MARTINEZ: What I like about "Yer Blues" is that it's an actual Beatles' song. All the Beatles are playing the instruments they're supposed to be there. Paul's not playing drums. John isn't playing bass. I think everyone's doing what they're supposed to do. That's why it sounds so good.

INGLES: Ringo always liked "Yer Blues," he said, because it was recorded with the four of them, in one room, mostly at the same time, which, clearly, wasn't the norm for this record.

SPURNEY: Yeah. If you listen to it, there's a really obvious splice in it, because they jammed for a really long time. When they were confronted with this ten-minute-long song, they had to cut it down to a more palatable length. There's a drum fill that goes, "tick ah tick ah tick ah!" Then it goes back into the original riff from the song.

MARTINEZ: It's musically very clever. In the verses, I believe it's three-four. It's a very slow, blues-y dirge, but then it kicks into almost "Heartbreak Hotel," four-four breaks. It's unpredictable, in that sense, and I really like that.

SPURNEY: And it's got the allusion to the Dylan song, "Ballad of a Thin Man," which confused me for the longest time. I didn't know what Lennon was singing. I finally saw the lyrics, printed out. He says, "Feel so suicidal, just like Dylan's Mr. Jones." I could never figure out what he was saying.

INGLES: "Birthday" comes first.Rob Martinez?

MARTINEZ: "Birthday" is an iconic song. This shows just how lofty the Beatles had gotten, by 1968, where Paul McCartney would write a song to, possibly, supplant our traditional birthday song. I think he did a pretty good job. It's fun to do and I always try to play that one at birthdays.

SPURNEY: My understanding is that they took a break from working on the album. They went to Paul's house, which was very close to the studio, because they all wanted to watch "The Girl Can't Help It," this great, 1950's rock and roll movie, title song by Little Richard. They were also psyched by seeing all the heroes of their youth in this movie. They said, "Let's go back and knock off a quick, '50s, rock and roll number." It was put together really quickly.

INGLES: Yoko Ono and Pattie Harrison are credited with backup vocals on this, too.

SPURNEY: Yeah, you can hear; it's those terrible "Birthdays."

"Birthday" and "Yer Blues" play.

INGLES: There's John Lennon's "Yer Blues," and "Birthday" ahead of that. "Yer Blues," Scott?

MacNICHOLL: Once more, John, we fall into that grinding blues. I can only think that he was listening to Muddy Waters a lot. It's real, tortured soul music. It's a real grind. It's grunge, long before there was the term, "grunge."

INGLES: I think Cream was hot then, and influencing the heavier sound, too.

URBANO: I'm going to stand with Suzanne, whenever she says, "What ever happened to the Beatles?"

INGLES: I think I was listening to this album a lot. But I think I started listening to it more religiously when I got to be 18, 19: some of the angst and despair that was, frankly, in some of those John Lennon songs was finally getting around to speaking to me.

KRYDER: I can remember when I was 19 or 20, wanting to skip through and just listen to the raunchy, depressing songs.

INGLES: We're going to close out this hour of our show with "Mother Nature's Son." Steve Turner, what's the story behind this one?

TURNER: It was written by Paul in Rishikesh, the result of a lecture by the Maharishi, which must have been to do with nature. He was thinking of a song by Nat King Cole, as well, called, "Nature Boy," which he'd always liked when he was a kid. Paul was a great nature lover. Although he grew up in Liverpool - you think urban, city - but you only had to go a few miles outside of where they lived in Liverpool and you had countryside. You could see the mountains of Wales from the high points around. He always loved nature.

INGLES: John Spurney, something on "Mother Nature's Son?"

SPURNEY: It's another beautiful, finger picking song. It's another, great example of a beautiful chart by George Martin: this beautiful, brass chart that compliments Paul's song. It's another, incredibly beautiful song.

INGLES: Douglas, did you want to come in on this?

GRANT: My impression of the arrangements on "Mother Nature's Son" is that it lies just about half way between "Martha, My Dear" and "Blackbird." They sound like they may even be a suite of three.

GANS: You're saying that "Mother Nature's Son" is a stylistic bridge between the other two?

GRANT: Yes.

GANS: Interesting.

"Mother Nature's Son" plays

INGLES: We're almost at the end of our second hour: not enough time to squeeze in another song, really, but maybe we could talk a little bit about this package. What did you guys make of this all-white album design?

MacNICHOLL: It was different. Here, they'd been so explosive, in colors and music in their previous releases. Suddenly, there was this slice of bread.

INGLES: Because Sgt. Pepper, Magical Mystery Tour, Yellow Submarine couldn't have been more colorful, more psychedelic. And then, this comes along.

PARKIN: When I first saw the White Album cover, I thought I had a promo copy in my hands: it had been released prior to the cover art having been completed.

INGLES: The design was suggested by artist, Richard Hamilton. I wonder if he got credit or paid for it, this simple design. What about this poster, and these color, 8x10 photographs of each member of the band that came into it?

MacNICHOLL: High quality.

KRYDER: Right. High quality, individual photos.

MacNICHOLL: Key word, "individual." No group photos.

KRYDER: The end of the Beatles! Dammit! Where's the Mop Tops? I just want them to cut their hair and get the matching suits on again. They're freakin' me out!

INGLES: We have the rest of Side Three and all of Side Four yet to come in our final hour of our program. More from the Beatles' White album and more from our panel, coming up. Special thanks to John Oswick. Our engineer is Roman Garcia. Thanks to KUNM in Albuquerque, New Mexico, too. I'm Paul Ingles. I hope you can join us for the next hour of "The White Album Listening Party."

HOUR THREE

INGLES: You've dropped in on "The White Album Listening Party," a bunch of Beatles fans and musicians are re-experiencing the Beatles' 1968 release. In the studio with me are several DJs, past and present, program hosts from public radio station KUNM here, in Albuquerque. We have the lights down low and are listening to the record in much the way many of us did back in 1968, '69, '70. We're listening to it, talking about it, trying to figure it out. We're going to hear many of the tracks on Record Two. Let's have you each introduce yourselves around the horn here, one, more time.

PARKIN: I'm Travis Parkin.

URBANO: I'm Lucio Urbano.

MacNICHOLL: I'm Scott MacNicholl

KRYDER: Suzanne Kryder

INGLES: We also have a panel of musicians standing by with us, both here, in the studio and across the country, helping us to tune our ears to specifics about the music and the lyrics.

SPURNEY: Hi, My name's John Spurney. I'm a musician and composer in New York City.

KRUGER: My name is Kristy Kruger. I'm a singer songwriter from Dallas, Texas.

GRANT: This is Douglas Grant. I'm a musician, recording engineer and producer in Tucson, Arizona.

GANS: My name is David Gans. I'm in Oakland, California.

MARTINEZ: I'm Rob Martinez and I live in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

INGLES: Finally, Steve Turner, author of the book, A Hard Day's Write: the Stories Behind All the Beatles' Songs is with us on the line from London. Steve, we pick up on Side Three of the White Album now with the song, "Everybody's Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey," which, I guess, would be the longest title of any Beatles' song. What's the story on this one?

TURNER: That was about John and Yoko and, I think, was about the turmoil they were caught up in. Yoko was not a welcomed guest, in the eyes of the other Beatles. It was the first time a woman had come into the Beatles' set up and not been willing to be just a girlfriend: to see the Beatle at appointed times. She actually wanted to be in the studio and make a contribution, even wanted to help out, writing lyrics. They didn't really like it. That spelt the beginning of the end. The "C'mon, c'mon, c'mon" at the beginning was taken from a track by the Fugs, called "Virgin Forest." It was a chorus on the beginning of that, which, I think, inspired that part of the song.

SPURNEY: The thing I love about the song is that someone plays a fireman's bell, throughout the entire song. My understanding is it's the same bell that you hear on "Penny Lane." It was lying around in a cabinet at Abbey Road. Just the craziness of someone, taking this incredibly loud, fireman's bell and just wailing on it, through the entire song!

GANS: In the Beatles' Recording Sessions book, they talk about this song as having been recorded. And then, they sped up the tape when they made their reduction mix, which means that the tempo and the pitch both wound up a lot higher than they were to begin with, which gives it that extra frenzied thing. That brings up one of the amazing things about this record and what the Beatles did. They were working with incredibly limited tools. During the making of this record, they found out that there was an eight-track machine, somewhere in the building. The bureaucracy had not authorized it for use. They began this, as they had Sgt. Pepper, Revolver and all their previous master works using a four-track machine and mixing things down into stereo pairs, and then adding more material to it. This makes the miraculous, magical awesomeness of it even more so, because they were able to do this with incredibly primitive tools, by today's standards.

"Everybody's Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey" plays

INGLES: "Everybody's Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey:" a song I've always loved. I'm looking it up here who's responsible for the fire bell. It says George Harrison was responsible for it.

URBANO: What's fascinating to me is George Harrison. Everyone, of course, can admire Lennon and McCartney. But George Harrison, his style of guitar playing.

INGLES: Travis?

PARKIN: "Me and My Monkey" really was a harbinger of what was to come from John Lennon in later years: the angst in his voice. When I listen to that song now, it almost sounds like it was something Lennon put out ten years later.

INGLES: Yeah. I think, in contrast to some of the other, the term we've been using is "scarier," tunes on this album though is there was a little element of joy in that whole thing. "C'mon, it's such a joy. Everybody take it easy, take it easy." I like that. Let's play the three songs that end Side Three now, back-to-back: "Sexy Sadie," "Helter Skelter" and "Long, Long, Long." Steve Turner, "Sexy Sadie" is the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi?

TURNER: If it wasn't actually written in Rishikesh, it was a result of Rishikesh. It was actually written, "Maharishi, you made a fool of everyone." They thought that was too libelous and so they changed it to "Sexy Sadie." There'd been a falling out between the Beatles and the Maharishi. They suspected him of, I think, exploiting them. He had ideas for doing a film. He wanted to use their name. The idea for taking ten percent of people's incomes which is ok if you're just a dentist or something, but if you're a Beatle, that's going to be a lot of money. They left under a bit of a cloud. "Sexy Sadie" was one of the first songs that were completed, after they left.

"Helter Skelter" was written, mostly, by Paul, as the result of a review, in one of the British music papers, of a single by the Who. This review said, "this is the most noisy, loud, fast rock and roll song you'll ever hear." Then, when Paul heard the song by the Who ("I Can See For Miles and Miles"), it didn't seem like that, at all. He thought, "Well, I'm going to write a song that would actually live up to that description." Helter Skelter is a kind of fair ground attraction. You climb up this tower and slide all the way down it, going 'round and 'round the apparatus. I guess Charles Manson didn't realize what a Helter Skelter was. That was another of the songs that he took as being personally addressed to him as a call to hide in underground caves while the revolution went on, and then come back when it was all over, and take over the world.

"Long, Long, Long" was written by George. The chord changes were based on "Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands" on Bob Dylan's Blonde on Blonde double album. It sounds like a love song. I guess it is a love song, in a way. But he said, in retrospect, it was a love song to god.

INGLES: "Long, Long, Long" has never received much notice. John Spurney, what do you like about that song?

SPURNEY: When I first heard the album, the song didn't really leap out at me. It's a very quiet, contemplative song. It requires a little effort to get into.

MARTINEZ: It sounds like something that could, eventually, be on "All Things Must Pass," just like "Sexy Sadie" sounds like something Lennon could have on one of his solo albums. The vocal is really down in the mix. I think that's why this song tends to get passed by. But it is really worth a listen. It's quintessential George Harrison.

SPURNEY: When I was a kid, "Helter Skelter" scared me so much. It was the most frightening thing I had ever heard. Of course, at the time I first heard it, it as predominantly associated with the Manson family. The book, Helter Skelter had just come out. There was, I think a movie, also called "Helter Skelter." They were all about the terrible, Manson family murders. So, when I first heard that song, I wasn't really a Beatles fan yet; I was just a little kid. It was like the aural equivalent of a horror movie. It frightened me to my very core. Now, I listen to it and it's a super rock song.

INGLES: For a period of history, that association really tainted it.

SPURNEY: Yeah. And it's a shame, because, obviously, it has nothing to do with that.

MARTINEZ: It's a great rock song. "Helter Skelter's" one of the fun songs we used to learn, back in high school. That descending, crunching guitar line on the first, two strings of the guitar: that just got you going, on its own.

SPURNEY: Yeah, and that riff! So much fun to play!

GRANT: Paul's vocal range, too.

MARTINEZ: Oh, man!

GRANT: And his dynamic abilities are definitely in the spotlight. He obviously still loves high voltage rock, and it's electrifying.

MARTINEZ: Yeah.

SPURNEY: And the Ringo, "I've got blisters on my fingers!"

MARTINEZ: It's iconic.

SPURNEY: Yeah.

GANS: Didn't I read in the recording sessions book that there were some takes of this that were, like, thirty minutes long or something?

MARTINEZ: I've read that, yeah. It's amazing. It just fades out and you think you're done, and it just fades back in to draw you back into it.

INGLES: "Sexy Sadie: I think Kristy Kruger had some thoughts about it.

KRUGER: One of the things I love about the Beatles is how they fuse so many different styles of music, whether it was blues, rock and roll, classical music. The riffs, the arpeggios that are happening. I love that element in the song. I also like the knowingness in the lyrics: taking a deep look at someone: "What have you done? You've made a fool of everyone." These are more - I don't want to say "judgmental," because that sounds negative - but these songs are promoting awareness of really looking into, reading into, seeing what somebody's about. I like that.

"Sexy Sadie," "Helter Skelter," and "Long, Long, Long" play

INGLES: There's "Long, Long, Long," "Helter Skelter" and "Sexy Sadie." Travis?

PARKIN: Looking back, I'm hearing heavy metal in "Helter Skelter." I'm hearing a precursor to the heavy metal days. And I'm not surprised that Charles Manson, of all songs, would latch onto that.

INGLES: It is wild and loud and crazy. If Paul was trying to create a song that would freak people out . . .

KRYDER: Lock up your daughters. That song freaked me out, man. I was like, ok, take all your Beatles albums and burn 'em. These guys are over the edge. They're gone.

INGLES: Scott?

MacNICHOLL: At this point in their career, they weren't the only ones on Mount Olympus anymore in the rock and roll world. They were along side Cream, Hendrix, the Stones, the whole Bay Area scene and L. A., the Doors. They wanted to play some rock and roll, do some different things.

INGLES: This is a great point, because the whole scene was about pushing the envelope and doing stuff that wasn't safe. Yeah, they were trying to keep up. We think of the Beatles as leaders. They were, because they had this incredible platform where everybody would be listening so closely.

URBANO: I see it that these guys were growing. They were still young. Look at the way they're taking the different genres, different styles.

INGLES: I talked with record producer, John Leventhal, about the Revolver album. He talked about the Beatles being so eclectic. It kind of started there. The personalities were emerging.

PARKIN: Sometimes, when I think of the Beatles, I think of them as different components of a single human being. I think of Paul McCartney as the head: the thinker, the person who makes sure the music is just commercial enough so that it'll sell. I think of John Lennon as being the heart of the band. I perceive George Harrison as being the spirit, or soul, of the Beatles.

INGLES: And Ringo's keepin' the beat.

PARKIN: And Ringo, as you say, was keepin' the beat. He was kind of like Every Man. He was the person in the band that we could relate to, that was not quite as god like as the others. He was more like us.

KRYDER: Was he like the muscles?

PARKIN: Maybe so. He was the physical body of the band, if you will.

KRYDER: Yeah, yeah!

INGLES: I'm Paul Ingles. This is "The White Album Listening Party:" about a dozen Beatles fans, hanging out in our virtual basement, reexperiencing the Beatles' 1968 collection of songs. Side Four starts with "Revolution #1," which was unusual, because all of us had heard "Revolution:" a raucous version of this same song, released as a single some months before. Then, there's this loping version of it on this record. Let's talk about "Revolution #1" on its own first, Steve.

TURNER: "Revolution" was John. At this time, the drugs and the Eastern mysticism – certainly with John – were disappearing. What was coming, in their place, was political revolution. He'd always been attracted to left wing politics and left wing activists had always been interested in John. He'd met with people like Tariq Ali, people involved in left wing magazines in the U.K. People like that were trying to see if they could get money or sponsorship from John. It's a song to those people. He's saying, "yeah, I've got the same ideas as you. I'd like to change the world. Wouldn't we all? But I don't believe in revolution that sheds blood. The kind of revolution I'm interested in starts within, starts within your mind, your consciousness." This song disappointed these left wing people, because they thought he was not joining them in the way they wanted. They didn't care to be told, "You gotta change your head. You gotta change your mind, instead."

INGLES: Many Beatles fans like some of one version and some of the other version.

KRUGER: I remember when I first heard "Revolution #1." It would have been in that Beatles class. I had never heard this other one, which turns out to have been the original. I liked it, quite a bit. It was a completely different treatment of the song.

INGLES: We half-way commissioned Douglas Grant in Tuscon to pull a George Martin of his own, and try to blend these two together. Douglas, what else did you learn about these songs, as you worked so closely with both of them?

GRANT: Listening to the single and working with it for awhile, I realized that it was one of the shoddiest productions that I think the Beatles ever released. It has some annoying edits in it. Technically, it's pretty rough. I think it's an extremely forceful song and recording, in spite of itself: definitely a strong message from John Lennon.

INGLES: Just for fun, let's listen to this "third" version, put together by Douglas Grant.

Douglas Grant "Revolution Mash-up" Plays

INGLES: What did you guys think of that?

MacNICHOLL: That was the two, blended together?

INGLES: Yeah, a fun stunt.

MacNICHOLL: When you're young, the first one – the single – kicked your ass. It was raucous. It was like the Who. It was in your face. It was . . .

INGLES: It was purposefully distorted.

MacNICHOLL: That was music for me, back then: 90 miles per hour. That's the way I wanted my rock and roll, 24/7. When the version came out on the White Album, it was, "what did they do to this?" I think Lennon was calling a lot of kids' in the streets bluff, while they were out there, in the streets, lettin' the horemones fly, rather than being out there for the revolution.

INGLES: He's asking them, "are you in, or are you out?"

MacNICHOLL: Right.

INGLES: I heard John Lennon interviewed bout that once. It was a conscious choice, for him, to write those words. He said, "I'm not sure if I'm out or if I'm in.

Next, on Side Four of the White Album, "Honey Pie," "Savoy Truffle" and "Cry Baby, Cry."

TURNER: I suppose what you could say links those songs is a certain innocence. It shows the Beatles had one foot in the world of novelty songs, children's songs, the musical, I guess. "Honey Pie" was almost a tribute to the kind of music that Paul's dad used to like. Paul's dad played in a jazz band and grew up in the '20s and '30s. That was the kind of music he liked. Paul liked it, too. "Savoy Truffle" is a joke of George's. It's about – there used to be these boxes of chocolates called, "Good News." They all had different names, like "Cream Tangerine," "Ginger Sling" and "Coffee Dessert." "Savoy Truffle" was one of the chocolates in this box. "Cry Baby, Cry" was based on a jingle that John heard on TV. It's like a nursery rhyme, I guess. This was another thing that fascinated the Beatles. "Yellow Submarine" is kind of a nursery rhyme.

INGLES: "Cry Baby, Cry" from John Lennon: anybody want to toss something in on that one?

SPURNEY: To me, that song has such a fantastic groove. The verses are really swingin', and the choruses are very straight. McCartney's bass playing, particularly on the verses on that song is just exceptional.

INGLES: "Savoy Truffle:" I love those phat horns on this one. It's a cliché, I know, but it's got a good beat, and you can dance to it.

MARTINEZ: True.

SPURNEY: The great thing is that the horns are deliberately over-recorded, so they're distorted. It gives them a great, chunky rock and roll sound. Those Berry saxes: it's great.

MARTINEZ: I love "Savoy Truffle." I love that George Harrison writes a song about candies, pastries and sweets. As a songwriter, I regret the state of songwriting, at least on the corporate level where it's so rigid, where a song like that, today, I don't think you could get anybody to even listen to it. These guys had the leverage to put this kind of thing on an album. And it's a great song!

INGLES: John Spurney, what gets you about "Honey Pie?"

SPURNEY: It's another great example of George Martin's effect on this record. Paul came in with this 1920's pastiche, which is great, but I think so much of it is the saxaphone part that George Martin wrote, which sounds exactly like records of the 1920's. It adds an authenticity to what McCartney was doing. This is where you really see how the Beatles are a post modern phenomenon. They can take any genre and any style and mix it together into a new thing. They're not just a rock band. They're a rock band that can play songs that sound like 1920's songs. They can play blues. They can play R & B. They can play whatever, like baroque, country music. Any genre is ripe for their use.

Play "Honey Pie," "Savoy Truffle," "Cry Baby Cry"

INGLES: There, we have "Cry Baby, Cry," "Savoy Truffle" and "Honey Pie," John Lennon, George Harrison and Paul McCartney.

KRYDER: Gosh, I barely remember those songs. It's like you get down to the bottom of the bag of chips and it's all crumbs down there. What's left here?

Revolution #9 fades in beneath

INGLES: "Revolution #9" comes in at this point on Side Four: over eight minutes of taped sounds that John and Yoko had mixed together. Mesmerizing, disturbing: what else did any of you feel about this one?

TURNER: "Revolution #9" was really John's idea, although Paul had also been doing these kinds of cut ups with prerecorded tapes.

INGLES: There's a little flavor of that on "Tomorrow Never Knows" (on Revolver)

TURNER: Yeah. This was to the White Album, as "Tomorrow Never Knows" was to "Revolver," "What on earth's that? It doesn't really fit on a Beatles' album. It was as though they'd allowed themselves a few minutes to get completely wild and experimental. It's a collage of all kinds of tapes that they'd found, one of them being a tape of a voice that they'd found, saying, "number nine." I believe it was some sort of test for a music academy, or something. I guess this was question number nine.

KRUGER: One of the things that's incredible about that song is that, when you think of the White Album, it's one of the first songs that comes to mind.

GRANT: I'm not sure that we can call "Revolution #9" a song.

KRUGER: It's a piece of music.

GRANT: But I don't think it's a song.

KRUGER: It's a sound composition.

PARKIN: I think I pretty much listened to it one time and never bothered to listen to it again.

MARTINEZ: "Revolution #9" lets me know what it is like to be on an acid trip. I don't necessarily want to know what that's like.

KRYDER: It reminds me of Yoko's influence on him. As an avant garde artist, it helped him feel – I don't know. Maybe he was braver or something, to put together music that was like art.

GRANT: Part of the enjoyment that I got from that collage is trying to pick out the little bits that are buried. If you listen with just one channel, or the other, or you drop the middle out, you can hear some things that you can't hear, otherwise. Also, to try to identify: clearly, there's some classical music in there. A lot of it's run backwards, in loops. The piano bit in the beginning is Schuman that's played backwards. I have to give a tip of the hat to my mother, who helped to identify some of those pieces. There's a shortwave radio and all kinds of stuff.

MacNICHOLL: I enjoyed it because it was look for things. And the emergence of Yoko doing some of the female voices. "Hold that line," the sports references. Just the little things. You look forward to it: eight minutes of this cacauphony.

TURNER: Number nine was actually a favorite of John's. I think he was born on October 9th. He lived at number nine in Liverpool. Nine seemed to crop up quite frequently in his life, and he attached some kind of mystical importance to the number nine.

KRUGER: It's just a statement of musical freedom, getting incredibly creative, opening up those portals of the brain, putting it out there and letting consumers hate it or love it. I'm glad it's on there. I remember hearing it for the first time in that Beatles class that I had in college. I thought it was the weirdest thing I'd ever heard and this was in the '90s!

SPURNEY: It's the centerpiece of what the record is all about, which is this crazy quilt of different genres, ideas and approaches.

INGLES: "Revolution #9" ends and then, slowly, an orchestra builds up from beneath. The Beatles are about to say, "Goodnight." Steve Turner, what about this album closer?

TURNER: "Goodnight" is very sentimental sounding, schmalzy song written by John. "Revolution #9" and "Goodnight" are probably the most un-Beatles sounding tracks on the album. Ringo sang it. You see, John did write sentimental songs. He wrote "Beautiful Boy" for Shawn. He wasn't beyond writing that sort of thing. It sounds, slightly, like "True Love," the Cole Porter song, from the musical, "High Society," sung by Bing Crosby.

INGLES: I think of it as being the perfect end for the album, because it's an exhausting journey.

CHORUS OF VOICES: Yeah! Yes!

INGLES: We've all been through so much, and now, let's just take a little nap.

MARTINEZ: Goodnight, everybody.

KRUGER: It's a very cinematic album.

INGLES: Meaning lots of characters and lots of scenes.

KRUGER: Absolutely!

PARKIN: It does have a cinematic quality to it, I agree.

MacNICHOLL: Yeah.

INGLES: There's a quote in one of my books here. John Lennon gave it to George Martin to orchestrate and said, "Just make it Hollywood. I know it's schmalzy; go for it."

MacNICHOLL: It's the end credits to an acid trip. And they let Ringo sing it!

INGLES: I liked that. I don't know if I knew about the sweetness that I associate with Ringo Starr then; I think I just felt it. I still get a little sentimental, hearing it. Obviously it pulls at the heart strings, because that's what those kind of Hollywood strings are meant to do, but it gets me.

Play "Goodnight"

INGLES: Since we referred to this track as the one to roll credits over, I'll do that for our program, now. I want to thank my guests at KUNM in Albuquerque: Scott MacNicholl, Luciano Urbano, Travis Parkin, Suzanne Kryder and Rob Martinez. Also, thanks to John Spurney, Kristy Kruger, Douglas Grant, David Gans and Beatle author, Steve Turner. Thanks also to John Oswick. Our engineer is Roman Garcia. This program is not for sale, but can be heard again, online, at the Public Radio Exchange, where you can listen to, and review, all kinds of content, at http://www.prx.org Also, look for it at the nonprofit music site, http://coolstreams.org. I'm Paul Ingles. You can check out links to other reporting and programs I've done on the Beatles and other artists online at my website, http://paulingles.com.

Thanks for being with us for "The White Album Listening Party." Sleep tight.

RINGO STARR: Goodnight, everybody. Everybody, everwhere, goodnight.

Transcription by Rogi Riverstone © 2008 – Cedar Creek Studios, Inc. / Paul Ingles / Use with permission only. Contact paul@paulingles.com